ISLAMIC STATE (IS) does not hide its brutality. When it burns men alive or impales their heads on spikes, it posts the videos online. When its fighters enslave and rape infidel girls, they boast that they are doing God’s will. So when fugitives from IS-occupied Syria or Iraq say they are frightened to return home, there is a good chance they are telling the truth.

The European Union is one of the richest, most peaceful regions on Earth, and its citizens like to think that they set the standard for compassion. All EU nations accept that they have a legal duty to grant safe harbour to those with a “well-founded” fear of persecution. Yet the recent surge of asylum-seekers has tested Europe’s commitment to its ideals, to put it mildly (see article). Neo-Nazi thugs in Germany have torched asylum-seekers’ hostels. An anti-immigrant group is now the most popular political party in Sweden. Hungary’s prime minister, channelling his inner Donald Trump, warns that illegal migrants, especially from Africa, threaten his nation’s survival.

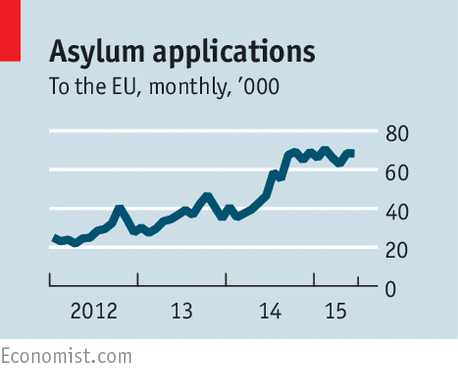

Some perspective is in order. Roughly 270,000 asylum-seekers have reached Europe by sea so far this year. That is more than arrived in the whole of 2014, but it is still only one asylum-seeker for every 1,900 Europeans—and many will be turned away. Much poorer parts of the world have seen far bigger inflows. Tiny Lebanon has welcomed 1.1m Syrians, roughly a quarter of the local population. Turkey has taken 1.7m. Tanzania, a country where the average income is one-fiftieth of the EU’s, has hosted hundreds of thousands of Congolese and Burundian refugees for decades, with few complaints. By contrast, when the European countries where Arab and African refugees first arrive (such as Greece and Italy) asked for help with looking after them, other EU states grudgingly agreed to take a paltry total of 32,256 over two years.

Doing well by doing good

Europe can and should do better. And not just for moral reasons but for selfish ones, too. Europe’s labour force is ageing and will soon begin to shrink. Its governments have racked up vast debts which they plan to dump on future generations. This will be harder if those future generations are smaller. Immigrants, including asylum-seekers, are typically young and eager to work. So they can help ease this problem: caring for the elderly and shouldering a share of debts they had no role in running up. Africans and Arabs are young. Europe can borrow some of their vitality, but only if European governments handle all types of migration more sensibly, which will be politically hard and require reform in labour markets, too.

Seeking safety: A flow diagram of asylum applications and rejections

The screening of asylum-applicants should be firm. Syria is a hellhole; Albania is not. But it should also be swift and generous. People who cross deserts and stormy seas to get to Europe are unlikely to be slackers when they arrive. On the contrary, studies find that immigrants around the world are more likely to start businesses than the native-born and less likely to commit serious crimes, and that they are net contributors to the public purse. The fear that they will poach jobs or drag down local wages is also misplaced. Because they bring complementary skills, ideas and connections, they tend to raise the wages of the native-born overall, though they may slightly reduce those of unskilled local men. And the migrants themselves benefit enormously. By moving to Europe, with its predictable laws and efficient companies, they can become several times more productive, and their wages rise accordingly.

Sceptics may retort that the cultural impact of migration is profoundly unsettling, and that Europe is neither willing nor able to absorb big inflows. Europeans recoil when they see crowds of unassimilated, jobless immigrants, as in parts of Paris or Malmo. And they fear Islamist terrorism, especially after the massacre at Charlie Hebdo and the disarming of a gun-wielding Moroccan on a French train last week (see article).

Not all who express such fears are bigots. And it is clear that monitoring of jihadist groups needs to be stepped up. But the answer to the broader question—how can Europe assimilate migrants better?—can be summarised in three words: let them work. This formula does well in London, New York and Vancouver. Jobs keep young men out of trouble. In the workplace, migrants have to rub along with locals and learn their customs, and vice versa. Which is why policies that keep newcomers idle are so destructive, from Britain’s restrictions on asylum-seekers working to Sweden’s rigid labour laws that make it uneconomic to hire the unskilled. A more open Europe with more flexible labour markets could turn the refugee crisis into an opportunity, just as America did with successive waves of refugees in the 20th century, including plenty from Europe. Let them in, and let them earn.

Copyright © The Economist Newspaper Limited 2015. All rights reserved.

See online: A bigger welcome mat would be in Europe’s own interest