No matter what publishers and writers do in terms of publicity, readers are still the final judges of what constitutes good literature. In a UK Guardian article this morning, inspired by a project by the Orange Prize and Vintage Classics, readers were asked what one book they would pass on to the next generation.

It was interesting to note the implicit and unquestioned Eurocentrism of the list and the reiterative recalling required in the production of a classic. Not one book by an African author made the list, indeed there were very few books of authors of colour there at all. I was inspired to ask a few writers to make their own recommendation by deliberately asking them to recommend one African book they would pass on to the next generation in full knowledge that one book or author’s ethnicity can never be enough.

Here’s what they had to say:

Eghosa Imasuen author of To Saint Patrick, a novel.

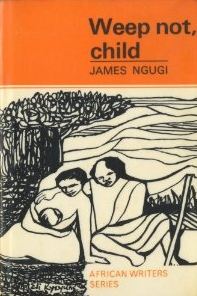

Weep Not Child, by Ngugi Wa Tiongo

I grew up in Warri, Delta State, in awe of my father’s collection of books. Ngugi Wa Tiongo’s Weep Not Child was my first stolen read. Worrying what daddy would do if he caught me soiling the pages with my fingers, I was both intrigued and terrified. As far away as Kenya was, these were characters I could relate to; as far away in time as the sixties were, these were characters I saw everyday in school, on the street, at church. I have read this book many times since those first days and nights of turning pages under the blanket with a torch. And I have come to realize what it did for me. It made the characters in my social studies textbooks come alive; it made them human, it told me that they could make, had made, mistakes. It showed me that history was never black or white, and that even in villainy, there were traces of humanity.

Nnedi Okorafor, author of Zahrah the Windseeker

Wizard of the Crow (Mùrùgi wa Kagoogo), by Ngugi wa Thiong’o

This great tome is a joy to read. It pays homage to the most traditional form of African storytelling, oral storytelling, on the level of language and cadence. It’s full of rebellion, riots and mayhem. The reader witnesses the African people of the mythical Free Republic of Aburiria bring down a dictator. It gives the big middle finger to corrupt politicians and sell-outs and shows them what they are: Monsters. The story is both modern and ancient. It features strong, active and compelling male and female characters. It addresses issues of gender within an African context. It shows the world as a place that is indeed full of magic and sorcery. I think all these things are images and ideas that every African youth should have percolating in her or his psyche.

Ivor W. Hartmann, author of Mr. Goop

The House of Hunger, by Dambudzo Marechera

Without doubt, The House of Hunger by Dambudzo Marechera. Now, there are a multitude of reasons why this is my first choice, but primarily it’s because in my opine he, and this book, towers above most authors, African or otherwise. Perhaps it can best be explained by a quote from the writer himself in The House of Hunger:

“Insist upon your right to go off on a tangent. Your right to put the spanner in the works. Your right to refuse to be labelled and to insist on your right to behave like anything other than what anyone expects. Your right to simply say no for the pleasure of it. To insist on your right to confound all who insist on regimenting human impulses according to theories psychological, religious, historical, philosophical, political, etc…. Insist upon your right to insist upon your right to insist on the importance, the great importance, of whim.”

Which are all sentiments I heartily agree with, and which were reflected in his life and works. As for other reasons, well, he was my countryman, and his writing was so far ahead of the times it was virtually prophetic, and as such, holds a great relevance to us now, and certainly for future generations, in our eternal quest for true freedom.

John Collins, author and musicologist

African Rhythms and African Sensibility, by John Chernoff

Deals with the philosophy behind traditional African drumming and its relation to society. This book influenced a lot of people, including westerners, like the rock muscian Brian Eno, and the Nigerian musician Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, who told me it was the best book written by a white man on African music.

John Chernoff spent many years in Ghana studying traditional drumming. Unlike many other books that try to quantify African drumming mathematically or just present objective descriptions of instruments, John’s book delves in the internal subjective and artistic side of drumming with an ‘insider’s’ eye. He helped open the ears and eyes of many New Wave rock artists of the 1980′s who were moving towards African music – which makes the book even more relevant to the present era with the international rise of World Music and Afropop.

Sade Adeniran, author of Imagine This

Zenzele: A letter for My Daughter, by J Maraire Nozipo

It was one of those books I could not put down once I started reading. The story goes deep inside Rhodesia (present-day Zimbabwe) and narrates the political and cultural struggles of Zimbabweans. What shines bright through the story is Amai Zenzele’s pride for her heritage, which she expresses so eloquently in a letter to her daughter who had left home to go to university in America. Each chapter is a lesson intended to warn Zenzele of the hardships she may face as a black woman studying in a foreign country.It struck a chord with me, because I live in a country where ‘Nigerian’ is sometimes seen as a pejorative term. To fit in, we embrace all that is Western and eschew our own culture. This book reminded me to be proud of my heritage and to remember where I came from.

Helon Habila, author Waiting for an Angel

Butterfly Burning, by Yvonne Vera

It is a beautifully written book. But most importantly it addresses the important issue of power and powerlessness in an African context, something that has always been important to me. Woman is here used to represent the subaltern class, the voiceless, who are sometimes driven to extreme acts in order to be heard. In this book a woman is confronted with an artificial limit set upon her hopes and expectations, and she commits a ritual suicide just to be heard. Sort of like in Tunisia when an impoverished street vendor, confronted with the sheer hopelessness of his situation, set himself ablaze in the central city of Sidi Bouzid last December.

Virginia Dike, educator and children’s book author

Arrow of God, by Chinua Achebe

Of course it’s an impossible question! There are so many candidates. From earlier years: Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country (my first African novel), Ayi Kwei Armah’s The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born, Sembene Ousmane’s God’s Bits of Wood to more recent titles like Helon Habila’s Measuring Time, Aminatta Forna’s Ancestor Stones, Buchi Emecheta’s The Slave Girl, and so many others. However, since I’m asked to pick only one, I would have to choose one that made a memorable and lasting impression. That is Chinua Achebe’s Arrow of God. I read it before I came to Nigeria and found in it such a vivid depiction of a society. But in particular I was struck by the depiction of a leader struggling to mediate between his society and the new world order, trying to find his way with integrity, and getting entangled by his ego. This made Ezeulu lose his objectivity and perspective, and led to personal tragedy, while his people quickly made their own arrangements and went on with their lives. I think this addresses a dilemma faced in every generation: holding to one’s principles and daring to play a role, while retaining one’s humility and perspective; having a realistic assessment of human frailty (of oneself and others) without giving up or giving in to cynicism or despair.

Sefi Atta, author of News From Home

Our Sister Killjoy by Ama Ata Aidoo

It’s the most dangerous book I’ve ever read by an African writer because Ama Ata Aidoo told the very people who were likely to publish the book—educated Westerners who were open to stories from Africa—exactly what she thought of them, and she wasn’t complimentary.

I’m surprised the book was ever published. In the West, dangerous writing is seen as a protest on social and political injustices in far-flung places. And in fact, that type of writing is quite welcome in the West. But if you dare to take on liberal racism and hypocrisy, as Ama Ata Aidoo did without flinching in Our Sister Killjoy, and to brag that as an African woman you’re freer and better off living in Africa, that would almost certainly be the death of your book in the West. She was brave.

Teju Cole, author of Every Day is for The Thief

News from Home, by Sefi Atta

A book for the next generation of African readers? I have two different responses to the question. One is that it’s almost better to read nothing at all than to read just one book. You need many different books, many points of view. Secondly, I don’t know if African readers should be thinking only of “African” books. Seems too narrow, somehow. The whole world belongs to us. Our perspective should be wide and generous.

Having said that, I would highly recommend to anyone, African or otherwise, Sefi Atta’s short stories, which were published as “Lawless and Other Stories,” in Nigeria and as “News From Home” in the U.S. Many of her stories can be found online. The work seems modest, but she’s actually a master of the short story form; with great skill she takes you into many of the complicated ways of being African today.

See online: African Literature: The Next Generation