The arts scene is booming in the self-declared republic of Somaliland but, as the BBC’s Mary Harper writes, the people who are pushing the cultural boundaries have come up against some opposition.

Circus boys in leopard skin print soar through the air, twisting their bodies into unimaginable contortions as the children in the audience clap and shriek in delight.

The acrobatic display is part of the entertainment at the annual Hargeisa International Book Fair where by day literature lovers, young and old, male and female, throw difficult questions at each other, fiercely debating delicate issues.

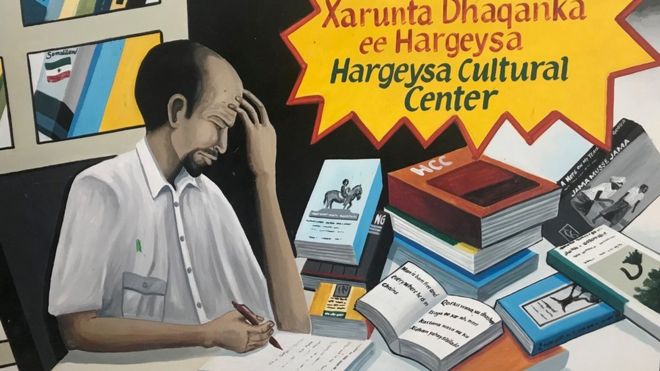

By night, hundreds crowd into the Hargeisa Cultural Centre for a concert by one of the self-declared republic of Somaliland’s most popular singers, BK, the music booming out into the surrounding neighbourhood.

But all this activity is hard won.

Although Somaliland is relatively peaceful and democratic compared with many other parts of the Horn of Africa, freedom of expression is under threat.

“We face a lot of hostility from some parts of the community,” says the director of the cultural centre and creator of the book fair, Jama Musse Jama.

“There are often calls in both traditional and social media for us to shut down. Some religious leaders attack us in their Friday sermons in the mosques.”

In mainly-Muslim Somaliland, some subjects are almost completely out of bounds. Many people are afraid to speak openly about the violent Islamist movement, al-Shabab, which has spread terror in the region for the past 13 years.

Although the group has not struck Somaliland for more than a decade, members of the security services say it is a real and present threat to the territory, which broke away from Somalia in 1991 after a lengthy civil war which led to the overthrow of the Siad Barre regime.

People speak about the group in whispers, often referring to it as the English Premier League club “Arsenal” to avoid drawing attention to themselves.

One area where freedom of expression is particularly at risk is the media, where the authorities are becoming increasingly repressive.

“Media freedom is not going in the right direction,” says Yahye Xanas, the executive director of the Somaliland Journalists’ Association.

“Journalists who report independently face the constant threat of illegal detention. In 2019 alone, 19 journalists have been detained and three media houses shut down. I was even summoned to the presidential palace for writing about the shortage of water in Hargeisa,” he adds.

‘Dangerous lies’

Mr Xanas acknowledges that there are serious problems with the media in Somaliland, including poor editorial standards and a lack of media ethics. As many journalists are not paid properly, if at all, some engage in corrupt practices.

Information Minister Maxamed Muse Diriye defends the detention of journalists, saying they spread dangerous lies.

“We have a very healthy media in Somaliland. About 15 TV stations are in operation and we have nine newspapers. Some media spread propaganda that threatens national security. When this happens, we have to intervene,” Mr Diriye says.

“Some of the people we arrest are not proper journalists,” he continues. “They are more like activists. Some are troublemakers, propagating Islamic extremism. This sort of activity goes way beyond journalism.”

It is not only journalists who face detention. In 2018, a young female poet, Nacima Qorane, was sentenced to three years in jail for writing a poem calling for the reunification of Somaliland with Somalia.

Mr Jama says that while conditions are becoming increasingly difficult for the media, there have been some improvements when it comes to culture as people challenge the authority of conservative Muslim clerics who believe that Islam forbids the playing of music.

“Things were even worse in the early 2000s,” he says. “People were not even allowed to play music at weddings.”

One place where culture is alive and kicking in Hargeisa is the Hidda-Dhawr, or “The Guardian of Our Heritage”, a sprawling complex of traditional Somali huts made from sweet-smelling dried grass.

Here, men and women gather to listen to live music, eat tasty Somali food, drink fresh watermelon juice and dance with each other.

‘Blooming like a flower’

The woman who set up Hidda-Dhawr, Sahra Halgan, is a singer and former member of the rebel Somali National Movement, which fought against the dictatorship of Somalia’s long-serving ruler Siad Barre.

She too has faced significant opposition.

“The authorities have tried to shut me down on a number of occasions. They have even sent soldiers to close my venue.

“Those who say I had no right to open Hidda-Dhawr know absolutely nothing about the war and the sacrifices I made. I carried a gun day and night during the long conflict that led to the creation of Somaliland,” Ms Halgan says.