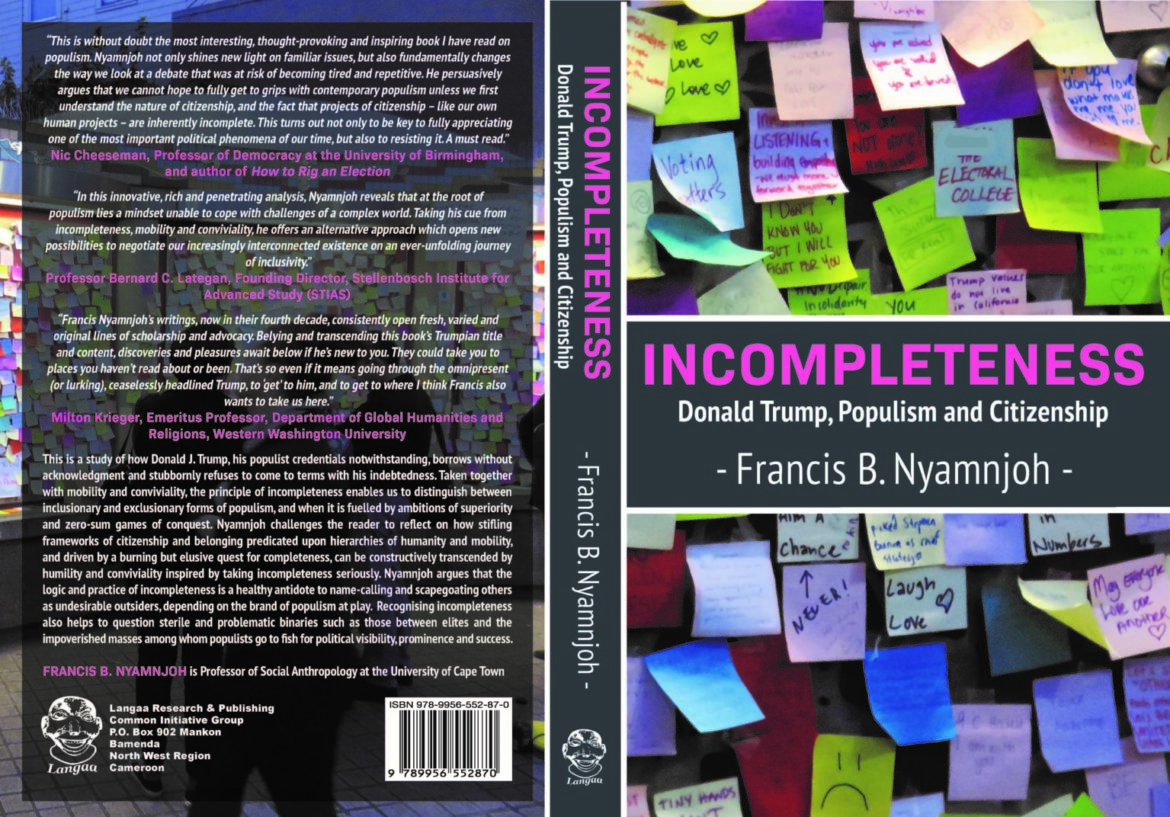

* Francis B. Nyamnjoh’s Incompleteness: Donald Trump, Populism and Citizenship is published by Langaa RPCIG (Bamenda, Cameroon), 2022. 395 pp., including bibliography, £39.60 (paperback), £39.60 (eBook), ISBN 978-9956552870

By Pierre Englebert*

I do not think I know of a more penetrating, original, irreverent (and yet fundamentally kind) contemporary thinker and political theorist as Francis Nyamnjoh. Whether fiction or essays, the books of his that I have read have had a profound impact on my thinking and opened my eyes to new ideas and analyses. I think, for example, of Married But Available, which brought up positionality in social sciences before it was a thing, and in the most hilarious way. I think also of #RhodesMustFall: Nibbling at Resilient Colonialism in South Africa, which addressed not only race but also the limitations of postcolonial sovereignty. Yet, hard to believe as it might be, Nyamnjoh has outdone himself with his latest book: Incompleteness: Donald Trump, Populism and Citizenship.

It is easy and common to write about Donald Trump with the many tropes of populism, the decline of liberal values, the changing economic fortunes of former majorities, etc. Nyamnjoh reviews these arguments and builds on them but takes us somewhere else altogether, eventually using Trump as a vector to make a broad and more momentous claim about citizenship, in his typical way of making surprising fundamental claims in the most unassuming way. For, while populism appears to be the topic of Nyamnjoh’s investigation, it is, in the end, an invitation to reflect on the important, neglected if not abused, notion of citizenship.

The way we typically think of citizenship is as a finite and exclusionary marker of identity. In the United States, particularly, we like to think of it in competitive terms—we like to be “# 1” and we make it increasingly difficult for others to join us. This view, Nyamnjoh points out, idolizes a sense of “completeness,” a belief that our society can be perfect and absolute and that it lies upon a foundation of dominance (Nyamnjoh makes it clear that the argument is not limited to the US but I restrict myself to what I know best in my discussion of it).

As we project this absolutist view of superiority across the world, so we practice it with each other at home. We fetishize inequality, the “encounter [of] others in unequal ways, conquering them and imposing one’s superiority.” This is in some ways the competitive environment of daily life in the US, with professional sports its omnipresent metaphor. Nyamnjoh sees this way of being, germane to “ambitions of conquest, domination or suppression,” as founded on a belief that “completeness” is possible, individually and collectively.

Nyamnjoh’s completeness is akin to a pure view of autonomy. One does not need others. Success is self-made. It is but a small step, if any step at all, from there to the arrogance that can come, he writes from “not recognizing one’s debts and indebtedness to others” (I was reminded of Obama’s 2012 remark “you didn’t build that” as I read Nyamnjoh’s words). As Obama did then, Nyamnjoh reminds us—and builds his argument on the notion—that incompleteness is always with us “even in one’s supposed superiority and autonomy.”

Nyamnjoh does not see this incompleteness as lacking in any way. It is not a status of inferiority. It is the often-obfuscated reality of life in society. We need each other, we cannot do it all alone. We are incomplete. And from this incompleteness come our societal bonds. From this incompleteness, Nyamnjoh rejoices, comes the possibility of conviviality. And so Nyamnjoh “embraces and celebrates” our incompleteness for it brings us together.

The humility that incompleteness calls for stands in contrast to the prevailing political mood in the US and to the foundations of populism. Hence, the danger that populism imposes, by its absolutism, upon the very fabric of life in society. This is where Nyamnjoh’s detour through citizenship is so important. Populism too is incomplete—it could not be understood without the convivial help of citizenship and incompleteness.

Nativism, autochthony, exclusionary claims to the benefits of the law seek to deny the realities or histories of others. They paint their claimants as complete, the others as unworthy, and they articulate along absolutist notions of citizenship that renege on our shared humanity. Nothing good comes out of them, including for those who claim them in the foolhardiness of their own perceived completeness.

In the end, Nyamnjoh’s core claim is that “being, becoming, belonging and citizenship” are “a permanent work in progress in an interconnected world of incompleteness.” Embracing our incompleteness paradoxically frees us by bonding us to others. And so, humility and conviviality is how we transcend exclusionary frameworks.

Armed with this wisdom, Nyamnjoh returns to Trumpism, “a testimony of crude exploitation of the fear of social change and the crisis of identity experienced by many whites” and, frankly, many non-whites too. Rather than a return to pure liberalism, which also hinges on forms of autonomy and completeness, Nyamnjoh suggests that the antidote lies in “a stronger sense of one’s dependence on others, a form of humble community.”

Not only does Nyamnjoh take us on a liberating intellectual journey, but he does so himself in the humblest of tones, in caring and good-natured ways, and with his perennial mischievous humor. Who else, after all, writes politico-philosophical essays that quote Tom and Jerry, Downtown Abbey and Amos Tutuola’s Palm-Wine Drinkard? A pure gem.

*Pierre Englebert is Professor of International Relations at Pomona College, Claremont, USA. Nyamnjoh’s Incompleteness: Donald Trump, Populism and Citizenship is available on Amazon.