JOHANNESBURG—Sustained economic growth in Africa has produced for the first time a broad middle class, one that cuts across the continent and is on par with the size of the middle classes in the billion-person emerging markets of China and India.

The rise of a middle class in the world’s poorest continent is a dramatic marker for the global economy. At a time when the U.S., Europe and Japan are struggling to grow, Africa is beginning to beckon as a consumer of what other nations produce, thanks in part to a young population more upwardly mobile than ever before.

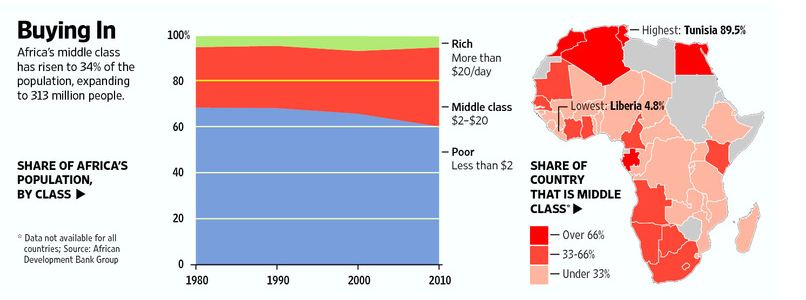

Over the past decade, the number of middle-class consumers in Africa has expanded more than 60% to 313 million, according to a new report from the African Development Bank Group. The study—one of the first efforts to document the contours of Africa’s emerging consumer class—brings into focus a potentially huge and enticing frontier market for global investors.

In the past few years, multinational appliance makers, telecommunications companies and retailers have piled into the continent in search of these consumers who, while still relatively poor, now have money in their pockets to spend, according to Mthuli Ncube, chief economist at African Development Bank Group, the parent of the funding arm.

“They are creating demand, and it’s driving growth,” he said.

Last year, the continent’s 313 million-person middle class— those who spend between $2 and $20 a day—comprised about 34% of the population. Its number rivals that of the middle classes in China and India, according to the study, which was reviewed by The Wall Street Journal. A decade earlier,the number was 196 million, it said.

Buying In

Africa’s middle class has risen to 34% of the population, expanding to 313 million people.

Poverty remains a predominant feature of Africa. Some 61% of Africa’s one billion people live on less than $2 a day, according to the bank. While many are getting more education and migrating from farms to better-paying jobs in cities, Africa’s population growth has undercut any dramatic reduction in poverty. The report estimates 21% of Africans earn only enough to spend $2 to $4 a day, leaving about 180 million people vulnerable to economic shocks that could knock them out of this new middle class.

Massive disparities persist. About 100,000 of the richest Africans had a collective net worth totaling 60% of the continent’s gross domestic product, according to the report, citing 2008 figures.

Still, Africa’s emerging middle class, and the accompanying consumer demand, is seen as an increasingly powerful economic engine, one that can complement the continent’s traditional reliance on agricultural, energy and mineral production and exports. About 21% of Africans are firmly entrenched in the new middle class, spending between $4 and $20 a day, the report said.

The bank’s report acknowledges that its broad grouping of Africa’s middle class includes the lower rungs of the income ladder. A stricter definition of spending $4 to $20 a day, it says, would yield a middle-class population of 120 million. Others have been even more conservative. A 2010 report from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, which sets the bar for a global middle class at daily expenditures between $10 and $100, estimated a middle class of 32 million in sub-Saharan Africa, which excludes North African countries.

The African Development Bank study, though, argues that its grouping includes genuine consumers—those living above subsistence level and spending money on nonessential goods.

In a separate report last year, McKinsey & Co. estimated that the number of African middle-income consumers exceeds the figure for India.

These new consumers are credited with cushioning Africa from the recent global economic crisis. The International Monetary Fund projects that sub-Saharan Africa, a collection of 47 countries, will grow 5.5% this year and 6% in 2012.

Documenting their numbers and consumption habits across different countries presented a challenge. Given scant official statistics, bank researchers mined information from airlines for travel, auto dealerships for car purchases, and a company that sells SIM cards to analyze mobile-phone consumers. They looked at school enrollments and noticed a rising number of Africans opting for private education, another indication of a robust new middle class.

The data paint a picture of a continent on the move, thanks to more open markets and a greater degree of political stability. New jobs—instrumental in China’s and India’s growth and urbanization—are spurring migration to cities and Africa’s wealthier countries.

Jossam Mass, a 32-year-old dressmaker from Malawi, moved to South Africa five years ago. Now his shop in Johannesburg’s Oriental Plaza is benefiting directly from the new consumer class. On a good day, he says, he sees 15 women who need tailor-made dresses for weddings or functions. Last week he produced 30 suits and shirts for the groomsmen of one wedding. “They do have money to spend,” Mr. Mass says of his customers. “And they sure like to spend it.”

The continent’s prospects have proved alluring for Wal-Mart Stores Inc., which has agreed to pay roughly $2.4 billion to buy 51% of South Africa’s Massmart Holdings Ltd., with plans to use the discount retailer as a foothold for continental expansion. Yum Brands Inc. recently said it wants to double its KFC outlets in the next few years to 1,200. In South Africa, Google Inc. and Microsoft Corp. are behind efforts to fund local entrepreneurs, with the hope that seeding African technology firms will grow their own businesses.

Nestlé SA is opening a new factory in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a central African nation repeatedly roiled by rebel insurgencies. Still, the number of people who can afford the Swiss food giant’s sachets of coffee and other price-sensitive products is on the rise.

“The potential is huge, but the business also has to be sustainable,” says Pierre Trouilhat, regional director for Nestlé based in Kenya. “The growth is now there.”

Still, some worry that U.S. businesses, in general, may be overlooking the opportunity.

Europeans, Indians and Chinese often have proved more willing to dive into new African markets.

Donald H. Gips, U.S. ambassador to South Africa, noted in a recent editorial in South African newspaper Business Day that Africa is now nearly as urbanized as China. That combination of urbanization and economic growth has been a boon for telecom companies—Africa now has more mobile-phone subscribers than the entire U.S. population.”Yes, there are risks to doing business in Africa,” he wrote. “However, here in Africa, right now,… the rewards could be as vast as the continent itself.”

The new consumers are people like Andrew Mafundo. The 35-year-old Ugandan advertising executive says he now carries a Toshiba laptop and a BlackBerry smartphone. He drives a Toyota Rav4 and is building a five-bedroom home in Kampala, the capital.

But the risks can’t be ignored. A series of violent elections in some of the continent’s biggest markets, for instance, threatens to reverse nascent economic gains for millions of Africans.

On Friday, more than a dozen people were shot in Uganda when security forces fired live rounds at protesters in Kampala, following the arrest of the country’s main opposition leader. Those protests are targeting President Yoweri Museveni, who has been in power for 25 years and was recently re-elected.

Earlier this month, voters in Nigeria, the continent’s second-largest economy after South Africa, rioted, burned and bombed buildings in violence that left hundreds dead.

The violence underlines the necessity of ensuring growth is accompanied with efforts to improve administration and increase official transparency, says Johannes Zutt, the World Bank country director in Kenya. “Africa’s prosperity depends on getting governance right,” he says.

South Africa shows the potential upside. After white-minority rule gave way to a multiracial democracy in 1994, a black middle class has emerged.

The country continues to deal with racial tensions, high unemployment and patchy public services, but a new generation of consumers is changing the economy. That phenomenon has surprised even those who are now a part of it, such as Itumeleng Mamabolo, a 28-year-old clinical psychologist in Johannesburg, who just returned from his first overseas vacation, in

Thailand. “I haven’t grown up with the luxury of having access to money and travel,” he says. “So it’s a bit surreal.”

—Jackie Bischof in Johannesburg and Nicholas Bariyo in Kampala, Uganda, contributed to this article.

Write to Peter Wonacott at peter.wonacott@wsj.com

Copyright 2011 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved

See online: A New Class of Consumers Grows in Africa: Market on Par With China’s and India’s