By Peter Osnos

The biggest publishing companies have an easy plan to save their industry: Get bigger

The merger of Random House and Penguin unquestionably represents an enormous change in the scale of publishing companies. It is a direct response to the power of the digital marketplace, but shifting ownership in the publishing industry is nothing new.

It is worth rolling back time to consider how these two leading publishing companies came into being. Random House is a conglomerate of once-independent imprints — Alfred A. Knopf, Doubleday, Crown, Pantheon, Ballantine, to name just a handful. They were acquired over decades by a succession of proprietors. From 1980 to 1998, the Newhouse family presided over the company, and its value rose from somewhere in the $60 million range to well over $1 billion, when it was bought by Bertelsmann, based in Gutersloh, Germany.

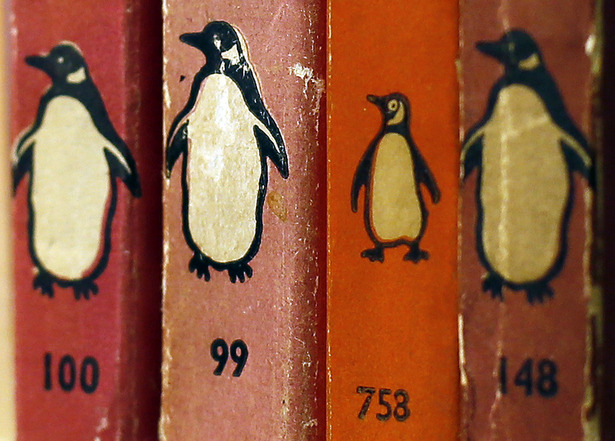

Penguin is closely identified with its British origins in the 1920s, but it too is composed of multiple imprints — Viking, Putnam, Dutton, and many others that were assembled in an inexorable process of growth, always intended to provide a stronger base for publishing as the distribution methods for books evolved.

Once, there were thousands of local booksellers, with owners who prided themselves on their particular tastes and the ability to feature those works that they found deserving. Over time, these community-based booksellers were challenged, and to a considerable extent overwhelmed, by national chains — Walden, Dalton, Crown (no relation to the publisher), and the superstores of Borders and Barnes & Noble. Beginning in the mid-1990s, Amazon carved out a new online supply chain by converting the purchasing experience from the time-honored browsing in bookstores to searching a vast selection of titles—eventually in the millions—that could be bought with a single click of the mouse. From the outset, Amazon substantially discounted books from list prices, and because of anomalies in the way early Internet commerce worked, without taxes.

With each year, Amazon’s range and market share expanded, while the brick and mortar chains and neighborhood booksellers scrambled to compete. The best of them became destinations for author appearances, book groups, and other specialized services. What was clearly a historic development took place in 2007, when the share of books to be read in e-book format began its rise to a mass market because of the immediate popularity of Amazon’s Kindle. The release of competing readers, such as Barnes & Noble’s Nook and Apple’s i-Pad, plus the surge in smart phones, fundamentally shifted the book marketplace towards a digital future and put increasing pressure on publishers in setting prices and determining the size of print runs.

In recent years, consolidation among publishing companies reached a level that was widely known as the Big Six: Random House, Penguin, HarperCollins, Hachette, Macmillan, and Simon & Schuster, all divisions of much larger companies. Together, they represent about half the total sales of trade books, with the balance spread among medium-size publishers, led by W.W. Norton, Bloomsbury, Scholastic and the Perseus Books Group, as well as thousands of smaller publishers, some of which are barely more than niche participants. With dizzying speed, the shift of digital sales meant that every publisher from virtually the smallest to the very largest has had to adapt.

So far, as I have written before, the industry, for all the challenges and uncertainties of what amounts to a revolution in reading habits has held its own. Books have always been supported by sales, unlike the advertising-based media, which have been driven to devise new revenue streams to compensate for the increasing fragmentation of their audience. There have been losers in this transition — the bankruptcy of Borders was the most notable — but books have maintained their place in the information and entertainment ecosystem, while newspapers, for example, have lost half their advertising revenue since 2006.

The Internet’s enormous variety of outlets has posed what seems at times insurmountable obstacles for newspapers and some magazines. Now we are entering a new era for books. Assuming Penguin and Random House successfully navigate the expected scrutiny of their combined size by authorities in Europe and the United States, the clout of this enormous publisher will enable it to shape its sales relationships — with Amazon in particular, but also Apple, Google, and Microsoft, all of which are developing platforms for books — with terms that understandably favor their interests over those of the publishers.

It is widely assumed that this type of consolidation will continue, with the likelihood of further mergers among the Big Six, or the acquisition of independent publishers in the belief that scale is an advantage in dealing with the giants of technology and e-commerce. Publishing has shown itself to be more resilient and even more innovative than outsiders (and even many insiders) predicted. This latest profound change will doubtless have consequences of all kinds for everyone in the book spectrum, from authors to readers. For those of us embedded in the continuing transformation, our conviction has to be that the evolution will be positive — a continuing book business providing works of all kinds, however and wherever readers want them. That is what we’ve always done and we will go on doing it.

Copyright © 2012 by The Atlantic Monthly Group. All Rights Reserved.

See online: A New Era for Books: The Random House-Penguin Merger Is Just the Start