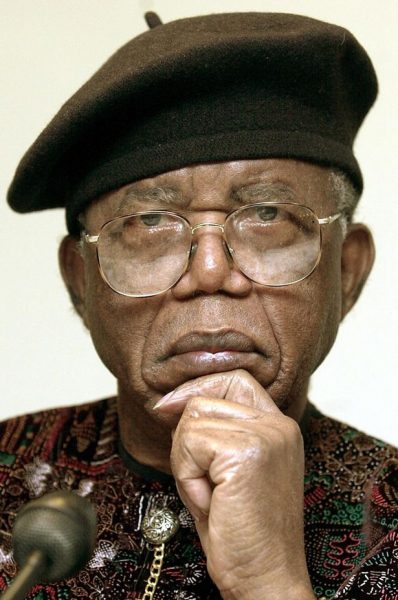

People of all ages crowded into the Timothy Dwight dining hall Wednesday, craning to catch a glimpse of Chinua Achebe as his hoarse but expressive voice floated through the crowd.

Achebe, a world-renowned Nigerian writer and professor of Africana studies at Brown University, read several of his own poems in front of a standing-room only audience. Available seats were all taken 15 minutes before the event was scheduled to start, so many attendees stood in the back or even crowded into doorways hoping to hear Achebe speak.

African American studies and English professor Elizabeth Alexander introduced Achebe to the enthusiastic crowd as the “indisputable father of modern African literature.” Alexander, who delivered a poem at President Barack Obama’s inauguration in 2009, said introducing Achebe was “bigger” than other “big” things she has done before. Achebe has written more than 20 books, including novels, collections of short stories and collections of poetry. His novel “Things Fall Apart” is the most widely read book in modern African literature, and has been translated into more than 50 languages.

Achebe chose to read a selection of his poems Wednesday, rather than giving a talk about his life and career. He explained that the poems he had chosen to read were inspired by the anguish caused by the Biafran War, a civil war in Nigeria that lasted from 1967 to 1970, in which the region of Biafra tried to secede and was eventually forced to rejoin Nigeria. Achebe emphasized the suffering that Nigerians, especially children, endured during this time.

Achebe read 10 poems in English and then repeated his final poem in his native Igbo. One of Achebe’s poems, “Refugee Mother and Child,” described a scene in a refugee camp in which a mother lovingly combs what remains of her emaciated child’s hair, even as mothers around her succumb to indifferent numbness and no longer interact with their children. The poem ends with Achebe’s inference that the mother’s ritual of combing her child’s hair could have been a simple daily occurrence before the war, but “now, she did it like putting flowers on a tiny grave.”

Three students interviewed after Achebe’s reading said they enjoyed the event, which was advertised as a lecture, though they had not realized Achebe would be reciting poetry rather than speaking about his life and experiences. Kavi Anandalingam ’13 said she would have preferred for Achebe to strike a more even balance between reading his poems and speaking about his career.

But for two students interviewed, the highlight of the afternoon was Achebe’s reading of his final poem in Igbo. The poem, an ode to an Igbo poet who had died as a soldier, was written in the style of an Igbo tradition to mourn a friend.

“Even though hearing it in English was nice, the intonation in his own language was so interesting to hear,” Maddy Buxton ’13 said.

Achebe came to Yale as a guest of the Chubb Fellowship, established in 1936 through an endowment provided by Hendon Chubb, class of 1895. The Chubb Fellowship has brought many prominent speakers to Yale, including presidents Harry Truman, Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush ’48.

See online: Achebe’s poetry packs TD dining hall