The question of language choice in African literature has caused significant ripples in the pool of literary criticism. The genesis of this discourse dates back to Obiajunwa Wali, who in 1963, wrote an article titled “The Dead End of African Literature” (Transition 10, 13-15) in which he argued that “the whole uncritical acceptance of English and French as the inevitable medium for educated African writing, is misdirected, and has no chance of advancing African literature and culture” (Quoted in Olaniyan & Quayson, 282). He further pointed out that until African writers accept the fact that any true African literature must be written in African languages, they would be merely pursuing a dead end. Wali even sounded a fatalistic note when he opined that “African languages would face inevitable extinction, if they do not embody some kind of intelligent literature, and the only way to hasten this, is by continuing in our present illusion that we can produce African literature in English and French”(op cit, 284). These postulations have given rise to a groundswell of contentious, even tendentious discourses among writers and critics of African literature. The most vocal voice among them all has been that of prolific Kenyan writer Ngugi wa Thiong’o.

In his seminal work, Decolonizing the Mind: the Politics of Language in African Literature (1986), Ngugi argues over and over again that to qualify as African, African literature has to be written in indigenous languages. As he puts it, “Literature written by Africans in European languages… can only be termed Afro-European literature; that is, the literature written by Africans in European languages” (Decolonising, 27). He describes his return to African languages in his fictional writing as “a quest for relevance” (87), noting that the use of indigenous languages in fictional writing is a liberating venture that enables Africans to see themselves clearly in relationship to themselves and to other selves in the universe. Thus, Ngugi’s rhetoric broaches the most urgent problematic of postcolonial African writing: the issue of how language (medium) becomes the message in a work of literature. It is a logocentric approach that puts a premium on words and language as the fundamental expression of external reality. This paper seeks to shed light on the language question in African literature. It delves into the contradictions inherent in Ngugi’s posture in favor of the unassailable position of indigenous languages in contemporary African fiction.

It is true that language embodies all the great moral, gender, philosophical, and in fact, physical issues humanity has grappled with from time immemorial. Language has been exploited by fictional writers to all intents and purposes, ranging from language as deconstruction in Orwell’s 1984 (1977), language as a room without a view in Kafka’s The Trial (1937), to language as a gap through which reality escapes in Robbe-Grillet’s Le Voyeur (1955) or from cyclic language as unmaking in Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude (1982), language as seduction and disillusionment in Nabokov’s Lolita (1955) to language as an expression of otherness in Nganang’s Dog Days (2001). There is always a “sense of carnivalesque enjoyment in the pyrotechnical properties of language-as-narrative,” to borrow words from André Brink (Quoted in Olaniyan & Quayson, 333-9).

However, to reduce the problematic of postcolonial literature to the question of language seems to me an untenable argument. Although I understand where Ngugi is coming from, and see the importance of promoting the use of indigenous languages through writing, I can’t help but think that his argument is completely circular and that he seems to contradict himself all too often. Africa has so many languages. In my home country, Cameroon, one can count over 200 languages. If one writes in one of these languages, how would the people from the other linguistic communities be able to read the books? Only the few speakers of the language in which the literary works are written would have access to the message.

I think the most important aspect of this contradiction is Ngugi’s decision to translate his books originally written in his mother tongue, Gikuyu, into the English language for the purpose of widening his readership. His latest novel,Wizard of the Crow (2007) was written in Gikuyu and later translated into English by Ngugi himself. He is so terribly against writing in English, yet we are reading his books in English! Ngugi’s stance on language is pretty inflexible, or too inflexible, in this era of globalization.

I don’t mean to be at all offensive, but I feel his stance is a little hypocritical in that after condemning writing in European languages, he still uses English to educate people about this. Decolonizing the Mind, his tool of combat is written in English! I’m bothered every time I read something written by him in English or hear him speak in English. Naturally, I’m not saying he shouldn’t write or speak in English, but doesn’t he see why it is somewhat necessary to do so? A proverbial expression in my mother tongue cautions against destroying the tree whose fruits you savor.

The mere fact that his indigenous-language fictional works have been translated into English so that it may be read by a global readership and Africans who don’t speak Gikuyu makes Ngugi’s frivolous argument a nonstarter. His latest book, Dreams in a Time of War: A Childhood Memoir(2010) which I reviewed not long ago is written in English! Ngugi is aware that he needs to reach a broader audience/readership; therefore, he writes in English. Isn’t this an indication that his pontifications against the use of imperial languages in African literature are spurious? If he only wrote in Gikuyu, wouldn’t he unquestionably have a limited readership?

In one of his essays “The Language of African Literature” (Decolonizing the Mind, 4-33), he endeavors to account for the rationale behind writing African literature in European languages, which includes a broader reading audience, publishing/distributing opportunities, and the majority of awards that are only given to works written in European languages. What does this say about his dogged determination to write only in his mother tongue? Ngugi finds it hard to stop writing in English or translating his own works into English because he is a product of the same linguistic/cultural dualism that nourishes his creative genius. I believe that he is merely resisting the psychological effects of the perplexities that arise from this ambivalence.

What would happen if Mungaka, an indigenous language spoken in the grassfields of Cameroon, became very popular and a French writer began writing their books in this native tongue? Would these books still be classified as Mungaka literature regardless of the French content of the works? How about a Kenyan who grows up speaking Gikuyu and later learns Japanese and starts to write fiction in this Asian language? Would his works be Kenyan or Japanese? Because intriguing questions like these are bound to arise, creative writers need to give serious thought to the language question in literature.

I certainly comprehend the importance of writing in African languages for the purpose of safeguarding cultural heritage. I have written in Cameroonian Creole (Pidgin), Camfranglais, and Hausa in my attempt to transpose not only the speech patterns and mannerisms of Cameroonians into the written medium but also to underscore Cameroonian worldview and imagination. But to argue that one has to write in one’s mother tongue in order to earn a place in the ivory tower of African litterai seems to me lame contention. If African writers only wrote in their native languages, wouldn’t this alienate readers who only read in European languages? Wouldn’t alienation harbor grave consequences, especially from the pecuniary point of view?

Ngugi’s uncompromising position is only one side of an ongoing argument in favor of the decolonization of African literature (Chinweizu et al, 1983). Like Ngugi, Chinweizu, Jemie and Madubuike posit that the use of European languages in African literature is a perpetuation of the neo-colonialist tendencies that seem so pervasive in African economies, politics and cultures. Aruging along similar lines, Ngugi observes that there is no difference between a politician who argues that Africa cannot dispense with imperialism and an African writer who believes that European languages are indispensable. As he puts it: “I believe that writing in Gikuyu language, a Kenyan language, an African language is part and parcel of the anti-imperialist struggles of Kenyan and African Peoples”(Quoted in Olaniyan and Quayson, 302).

On his part, Chinua Achebe observes that for him there is no choice; he has to write in English: “But for me there is no other choice. I have been given the language and I intend to use it” (Morning Yet on Creation Day, 62). If you want to get reward for your hard labor (writing), you need a wider audience.

Achebe’s writing does not usually conform to the European language idiom and syntax not because he is not proficient in English but because he is smart enough to manipulate the English language to bear the weight of his Igbo imagination and sensbility. As he puts it: “The price a world language must be prepared to pay is submission to many different kinds of use” (op cit, p.61). Though written in English, his novels are very rich in African tradition. He has the tool and uses it in a way that serves his purpose. How many people would have read Things Fall Apart (1958) or Arrow of God (1964) if they were written in Igbo? Achebe’s domestication of the English language in these novels is done with a seamlessness that demonstrates his dexterity as a creative writer; not his inability to utilize “standard” English. Achebe’s commitment to the promotion of a Nigerian identity in his Europhone novels lends credence to the fundamental truth that African literature need not be written in African languages in order to convey an African message. What matters, in essence, is that the African writer be responsible for promoting an image of Africa, positive or negative, using whatever tools are at his/her disposal. For Ngugi this is done through the use of Gikuyu.

For Achebe, Soyinka and francophone writers like Kourouma, Nganang, Fonkou, and Boni, it is the indigenization of language that makes the task feasible. These writers are able to (re)mold European languages and make them feel and sound African. I believe that transgressing the grammatical canons that govern the usage of European languages and incorporating different aspects of African language aesthetics is a tremendously effective way to get ideas across to readers. Kourouma achieves this feat in The Suns of Independence (1981).

African Literature written in European languages is African literature. Many attributes converge to produce a label for a particular brand of literature. Medium (code) of communication is only one aspect. Other factors namely, stylistics, content, situational dimensions, spatio-temporal matrices, to name but a few, are integral parts of the holistic message. It is disingenuous to limit the examination of a people’s literature to the ‘wrapping’ at the expense of other constituting factors. I do not think that the language in which a work of literature is written is really as important as Ngugi and Wali perceive it. What is more important is the message/content and the stylistic devices employed to convey intended messages. It does not matter which language writers choose to glean their signifiers from, all that matters is what is being signified. I feel that one should judge whether or not a novel is “African” by what is being signified, not by the language from which the signifiers are culled.

That being said, I continue to wonder whether Ngugi truly even believes what he is saying and if so, why is he still writing in English? What are his motivations for circumventing this issue? Outrage, inspiration, or captivating an audience? I believe denouncing Africans who write in European languages (himself included); Ngugi is simply seeking negative attention. Is he trying to draw attention to his works? Hasn’t he garnered enough notoriety as a dissent writer? I believe that Ngugi wants to be heard in the dissident tone of voice for which he is already notorious. Like Wali, does he really fear that African languages would be extinct if Africans don’t write in their mother tongues?

Just because we do not write in our native tongues does not mean that the languages are going to be lost! The question regarding what will happen to African native languages that are not written in is an interesting one, though. I think it takes more than just literature to make a language last. The whole debate on the interplay between orality and literacy has been fully examined by Walter Ong in his text Orality and Literacy: the Technologizing of the Word(1982) in which he points out that language perpetuates culture, and culture sustains language. As long as languages are orally kept alive they will survive, no question about that. The deleterious effects of the arguments against Europhone African literature is that they make African literature in European languages inherently second-rate. I’m sure Ngugi would balk at me for saying this, but in a way, he is doing the same thing the colonizers did to African languages—they brought their languages to Africa and attached a stigma to the use of native African languages. By raising African languages to an unquestionably higher pedestal, Ngugi is devaluing the work of African writers who write in English, French or Portuguese. I don’t know if he is necessarily discrediting them, but I do feel as though he is giving them a slap on the wrist, so to speak.

This discourse raises the question of relevance in African literature. Ngugi observes: “…the language question cannot be solved outside the larger arena of economics and politics or outside the question of what society we want” (Decolonizing, 106). How relevant are African literary texts to the rank and file— the proletariat and the masses to whom the message is often directed? Ngugi co-authored his first play Ngaahika Ndeenda (1982) in Gikuyu and later translated it into English as I Will Marry When I Want (1982). The original version was staged as a communal play in an open theatre. The local folks could identify not only with the language but also with the themes that undergirded the crafting of the play, notably misappropriation of land in Kenya under British colonial rule. The play also tackles the problem of neo-colonization. In brief, the play was relevant to Kenyans because it reflected their lived experiences.

All of Ngugi’s works of fiction are deeply concerned with existential problems, celebrations and conflicts in the lives of Africans. With this in mind it seems to me that Ngugi is caught in a terrible web, in that he believes that revolutionary literature has to be written in a language the people would understand. He seems to be saying that if literature is not written in the language of the people, the revolutionary among them will not be born.

In this case, the language of the people is very important. Yet, he reverts to writing in English without giving his readers cogent reasons why he does so. Do Africans want to continue to tell their own stories in foreign tongues? Do they want to continue to feed their children with stories about the marvels of western civilization at the expense of their own cultural values? Ngugi’s arguments may make sense when we come to terms with the fact that the search for new directions in our language policies should be viewed as an integral part of the overall struggle of Africans against imperialism in its neo-colonial stage. He contends that discourse on the politics of language in African literature cannot be dissociated from Africa’s struggle for liberation. As he puts it: “It is a call for the rediscovery of the real language… of struggle…” (op cit, 108). Ngugi certainly has a point when he underscores the imperialistic functions that language has been made to fulfill in Africa.

This notwithstanding, it seems to me that there are many more nefarious manifestations of imperialism that should constitute the focus of the liberation struggle in Africa. It is counterproductive to try to impose reductionist standards on how to judge African literature today on the grounds that we are waging a war against imperial forces.

African writers should be at liberty to write in the language(s) of their choice because our cultural values, worldview and imagination can only be shared with the external world through African literature written in European languages. I have no doubt that, on second thought, Ngugi wa Thiong’o would be prepared to modify the statements he has made so far about language choice in African literature, the more so because he continues to write in English after making these powerful statements. I fully support him on the issue of promoting the teaching of African languages in schools through well conceived curricular modalities. Even though (I’m sure) Ngugi has the best intentions in defending his position so passionately, his prescription has the potential to inhibit creativity to a certain extent because it is so restrictive.

The fact that African literature produced in European languages so far has been incredibly effective at communicating the message of resistance against neo-colonial oppression and cultural imperialism demonstrates the ingenuity of writers at using every available resource to assert their identity.

In a nutshell, the ongoing debate on language choice in African literature should not be perceived as an attempt to belabor the obvious. Given the history of colonization and its aftermath in Africa, this question is bound to recur in any forum where the raison d’être of fictional writing is the topic of discussion. It is important for Africa to have literatures written in indigenous languages to preserve traditional values and speak directly to fellow Africans. At the same time, we cannot subscribe to the fallacious logic of the unassailable position of indigenous languages in contemporary African literature.

I believe that there must be a balance between the inclusion of African-language literatures and Europhone literatures written by Africans in our corpus of literary works. In sum, this all goes back to the question: What makes a book African? The writer is African? The language is African? The message is African? Or all three? Though I agree that publishing houses should encourage the publication of African-language literatures, I also don’t think it is fair to discount a writer simply because s/he chooses to write in English, French, or Portuguese, etc. For many Africans, indigenous languages might provide the most natural mode of writing; others, though, may choose European languages for a variety of equally valid reasons. I would actually like to know what bothers Ngugi, Wali and ilk more—the fact that English is a colonial language, or the fact that by writing in English, an African writer is not using a native African language.

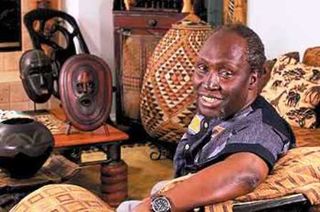

By Peter Wuteh Vakunta (University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA)

Works cited

Achebe, Chinua. Things Fall Apart. London: Heinemann, 1958.

_____________. Arrow of God. London:Heinemann, 1964.

_____________. Morning Yet on Creation Day: Essays. London: Heinemann 1975.

Brink, André. “Languages of the Novel: A Lover’s Reflections.” Olaniyan, Tejumola and Ato

Quayson. Eds. African Literature: An Anthology of Criticism and Theory. Oxford:

Publishing, 2007.

Chinweizu et al. Toward the Decolonization of African Literature. Washington D.C.:

Howard University Press, 1983.

Grillet, Robbe. Le voyeur. Paris: Editions de Minuit, 1955.

Kafka, Franz. The Trial. New York. A.A. Knopf, 1937.

Kourouma. Ahmadou. The Suns of Independence. London: Heinemann, 1981.

Marquez, Garcia Gabriel. One Hundred Years of Solitude. New York: Limited Editions Club,

1982.

Nabokov, Vladimir Vladimirovich. Lolita. Paris: Olympia Press, 1955.

Nganang, Patrice. Dog Days. Charlottesville: University of

Virginia Press, 2001.

Ngugi, wa Thiong’o. Decolonizing the Mind: the Politics of Language in African

Literature. London: Heinemann, 1986.

_______________. Wizard of the Crow. New York. Pantheon Books. 2006.

Ngugi, wa Thiong’o and Ngugi wa Mirii. I Will Marry When I Want. London: Heinemann,1982.

Olaniyan, Tejumola and Ato Quayson. Eds. African Literature: An Anthology of

Criticism and Theory. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2007.

Ong, Walter. Orality and Literacy: the Technologizing of the Word. London and New

York: Routledge, 1982.

Orwell, George. 1984. London: Penguin Books Limited, 1977.

Wali, obiajunwa. “The Dead End of African Literature.” Transition 10(1963):13-15.

© The Entrepreneur Newspaper 2010. All Rights Reserved

See online: Aporia: Ngugi’s Fatalistic Logic of the Unassailable Position of Indigenous Languages in African Literature