by Louisa Lim

NPR – (null)

Zhou Youguang should be a Chinese hero after making what some call the world’s most important linguistic innovation: He invented Pinyin, a system of romanizing Chinese characters using the Western alphabet.

But instead, this 105-year-old has become a thorn in the government’s side. Zhou has published an amazing 10 books since he turned 100, some of which have been banned in China. These, along with outspoken views on the Communist Party and the need for democracy in China, have made him a “sensitive person” — a euphemism for a political dissident.

When Zhou was born in 1906, Chinese men still wore their hair in a long pigtail, the Qing dynasty still ruled China, and Theodore Roosevelt was in the White House. That someone from that era is alive — and blogging as the “Centenarian Scholar” — seems unbelievable.

Pinyin, The ’Open Sesame’ Of Chinese

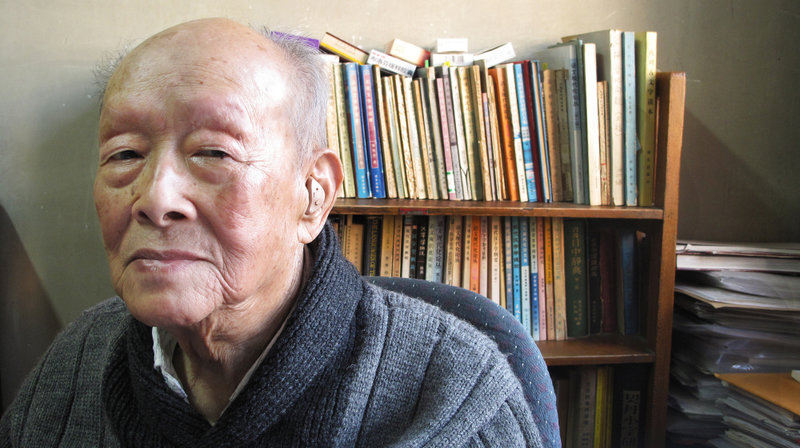

But despite his age, Zhou still lives in a modest third-floor walk-up. He’s frail but chipper, as he receives guests in his book-lined study. He laughs cheerfully as he reminisces, despite his complaints that “after 100, the memory starts to fail a bit.”

Zhou was educated at China’s first Western-style university, St. John’s in Shanghai, studying economics with a minor in linguistics. As a young man, he moved to the United States and worked as a Wall Street banker — during which time he even befriended Albert Einstein, although Zhou says their conversations are now lost in the mists of time.

Zhou decided to return to China after the 1949 revolution to build the country. Originally, he intended to teach economics in Shanghai, but he was called to head a committee to reform the Chinese language.

“I said I was an amateur, a layman, I couldn’t do the job,” he says, laughing. “But they said, it’s a new job, everybody is an amateur. Everybody urged me to change professions, so I did. So from 1955, I abandoned economics and started studying writing systems.”

It took Zhou and his colleagues three years to come up with the system now known as Pinyin, which was introduced in schools in 1958. Recently, Pinyin has become even more widely used to type Chinese characters into mobile phones and computers — a development that delights Zhou.

“In the era of mobile phones and globalization, we use Pinyin to communicate with the world. Pinyin is like a kind of ’Open sesame,’ opening up the doors,” he says.

Political Progress Is ’Too Slow’

Although official documentaries by the state broadcaster have celebrated his life, Zhou’s actual position is more precarious. In the late 1960s, he was branded a reactionary and sent to a labor camp for two years. In 1985, he translated the Encyclopaedia Britannica into Chinese and then worked on the second edition — placing him in a position to notice the U-turns in China’s official line.

At the time of the original translation, China’s position was that the U.S. started the Korean War — but the encyclopedia said North Korea was to blame, Zhou recalls.

“That was troublesome, so we didn’t include that bit. Later, the Chinese view changed. So we got permission from above to include it. That shows there’s progress in China,” he says, adding, “But it’s too slow.”

At 105, Zhou calls it as he sees it without fear or favor. He’s outspoken about what he believes is the need for democracy in China. And he says he hopes to live long enough to see China change its position on the Tiananmen Square killings in 1989.

“June 4th made Deng Xiaoping ruin his own reputation,” he says. “Because of reform and opening up, he was a truly outstanding politician. But June 4th ruined his political reputation.”

Far from shying from controversy, Zhou appears to relish it, chuckling as he admits, “I really like people cursing me.”

Bold And Outspoken Criticism

That fortitude is fortunate, since his son, Zhou Xiaoping, who monitors online reaction to his father’s blog posts, has noted that censors quickly delete any praise, leaving only criticism. The elder Zhou believes China needs political reform, and soon.

“Ordinary people no longer believe in the Communist Party any more,” he says. “The vast majority of Chinese intellectuals advocate democracy. Look at the Arab Spring. People ask me if there’s hope for China. I’m an optimist. I didn’t even lose hope during the Japanese occupation and World War II. China cannot not get closer to the rest of the world.”

The elderly economist is scathing about China’s economic miracle, denying that it is a miracle at all: “If you talk about GDP per capita, ours is one-tenth of Taiwan’s. We’re very poor.”

Instead, he points out that decades of high-speed growth have exacted a high price from China’s people: “Wages couldn’t be lower, the environment is also ruined, so the cost is very high.”

Zhou’s century as a witness to China’s changes, and a participant in them, has led him to believe that China has become “a cultural wasteland.” He’s critical of the Communist Party for attacking traditional Chinese culture when it came into power in 1949, but leaving nothing in the void.

Still A Force To Be Reckoned With

He becomes animated as talk turns to a statue of Confucius that was first placed near Tiananmen Square earlier this year, then removed.

“Why aren’t they bringing out statues of Marx and Chairman Mao? Marx and Mao can’t hold their ground, so they brought out Confucius. Why did they take it away? This shows the battles over Chinese culture. Mao was 100 percent opposed to Confucius, but nowadays Confucius’ influence is much stronger than Marx’s,” he says.

One final story illustrates Zhou’s unusual position. A couple of years ago, he was invited to an important reception. At the last minute, he was told to stay away. The reason he was given was the weather.

But his family believes another explanation: One of the nine men who run China, a member of the Politburo Standing Committee, was at the event. And that leader did not want to have to acknowledge Zhou, and so give currency to his political views.

That a Chinese leader should refuse to meet Zhou is telling, both of his influence and of the political establishment’s fear of one old man. [Copyright 2011 National Public Radio]

To learn more about the NPR iPad app, go to http://ipad.npr.org/recommendnprforipad

See online: At 105, Chinese Linguist Now A Government Critic