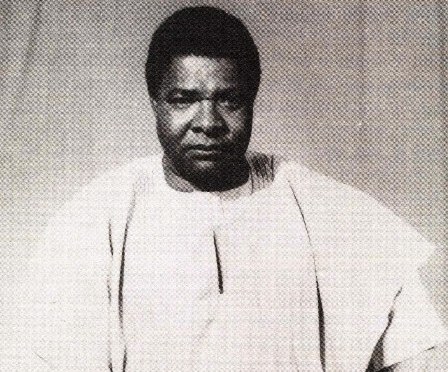

The death of Bernard Fonlon in an Ottawa room was completely overshadowed by the horror of the Lake Nyos disaster that occurred some thirty miles from his birthplace of Banso in the North-West Province of Cameroon. In some way, the very fact that he died in semi-obscurity is symbolically appropriate, for despite the accomplishments of his life, Fonlon was a humble man, who never really sought the limelight.

As others gained fame and notoriety, he labored patiently and effectively – as a government minister, as the editor of an impressive cultural journal, and as a teacher – to realize the lofty ideals he had ser for himself. He always defended the highest standards of excellence, and unlike many of his successful countrymen, he was never interested in amassing a personal fortune. In fact, he became an almost legendary exemplar of integrity and the modest life style in a country where conspicuous consumption is commonly regarded as a perquisite of success. Strangers who met Fonlon for the first time during the final decade of his life were not always immediately impressed with him. He was often drowsy. He tended to ramble. His opinion on most subjects had been formed years ago and seemed to resist change. Younger students complained that he had not kept pace with recent developments in African literature, and even his best friends had to exercise patience when he launched into the endless retelling of anecdotes from his past.

Nevertheless, few people ever met Fonlon without sensing that there was something more – something profoundly human – behind the avuncular stolidity of his manner. Perhaps it was a playful glint in his eye; perhaps it was a burst of impassioned rhetoric; perhaps it was the quiet wisdom of a man who, having imbibed deeply from many cultures, continued to believe that human dignity was possible in a chaotic and corrupt world. Whatever it was, this intangible quality made people aware that Bernard Fonlon was a presence. What many people did not realize was that he had been seriously injured in an automobile accident during the early 1970s. He lay in a coma for over a week at that time. He almost died. Afterwards he frequently complained of headaches, and the medicines he took to relieve the pain impaired his ability to concentrate. He felt tired, and he began to hope aloud that a younger generation of Cameroonians would assume some of the responsibilities he had for so long taken upon himself. The journal Abbia, which he had worked so hard to keep afloat for over twenty years, floundered and finally ceased publication. His lectures at the university became sporadic.

Nevertheless, people continued to admire him, for they could feel the spark of humanity in him. It was this spark that enabled him to respond with enthusiasm to the teachings of a Catholic missionary in Banso more than fifty years ago; in fact, much of his subsequent life makes sense in terms of the moral idealism he absorbed from Father Kennedy. The same spark gave him the courage to walk for weeks through the tropical rain forest to enrol in the seminary at Onitsha. It also gave him the courage to write an open letter to the bishop, pointing out ways in which African priests were treated less well than their European counterparts. This letter brought about his expulsion from the seminary three weeks before his scheduled ordination.

Yet, despite the racism of the colonial church, Fonlon never confused the ideals of Christianity with the practices of its corrupt adherents. The spark of humanity in him continued to inspire his efforts as he taught school in Nigeria, obtained his doctorate in Ireland (with one of the first dissertations on the awakening of the black consciousness), served the young Ahidjo government in many capacities (including that of gadfly and moral conscience), and taught the black literature he passionately loved. During all this time, Fonlon wrote poetry, essays about civic responsibility, editorials about the appreciation of literature, papers about bilingual education, speeches about political reconciliation. Much of his writing has been reprinted, although it has never been collected and edited in such a way as to reveal the genuine contributions he made to his country and to African letters. Fonlon accomplished a great deal during his lifetime, and he set a high standard for others to follow.

Although his greatest influence was undoubtedly on the lives of his fellow countrymen, he touched nearly everyone in important ways because that spark of humanity always glowed in him. He loved the region around Banso and always remained deeply attached to the culture of his people. At the same time, he opened himself to other cultures, and he committed himself unreservedly to the ideal of a unified Cameroon. His presence will be missed, and it is unfortunate that he never completed the memoirs upon which he was working at the moment of his death. With him died a great deal of knowledge, experience, and wisdom that might have been shared with others through the pages of his projected book. Bernard was a good writer, a good teacher, and a good statesman, but he was above all a good man.

By Richard Bjornson, The Ohio State University

See online: “Bernard Fonlon: In Memoriam”