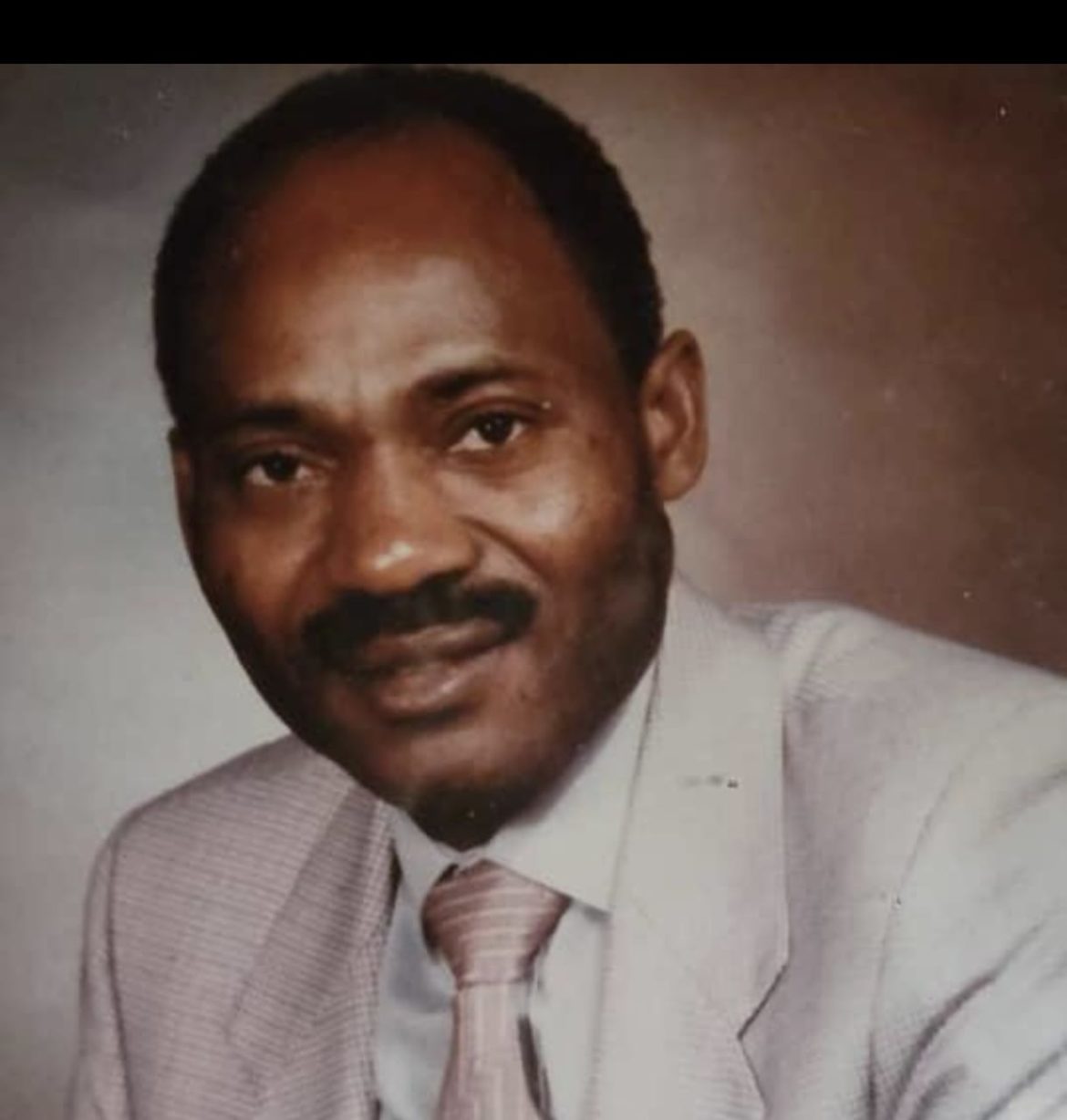

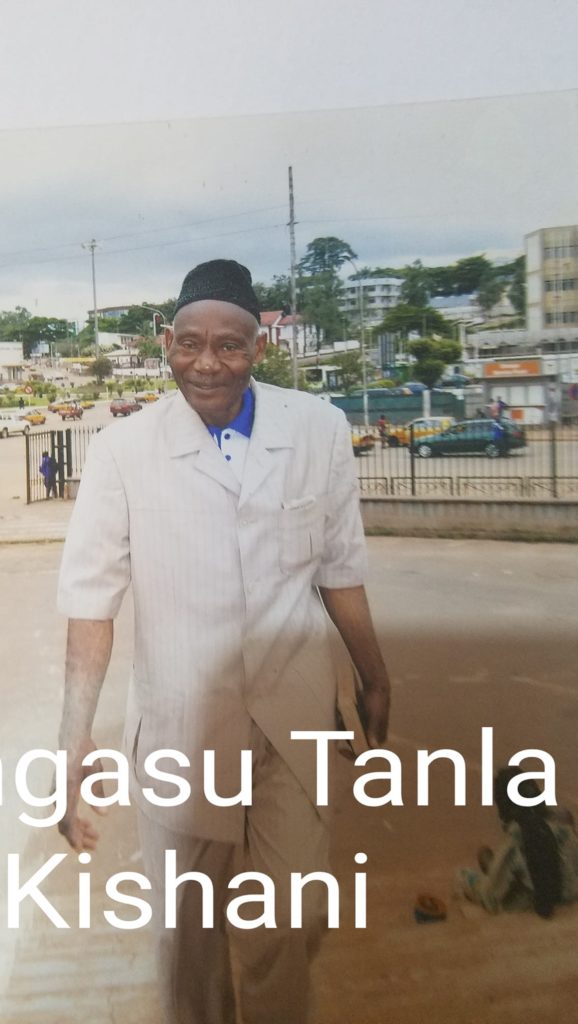

Professor Bongasu Tanla Kishani, a famous philosopher, orature scholar, poet, writer and indigenous language literacy promoter, of Nso origin in Cameroon, went to rest on Friday 23 February 2024. Prof Kishani was a very staunch promoter of African and Cameroonian cultures and languages and yet so humble and reachable. And I want to pay my respects to him in this write-up.

Let me begin with how I came to know this great intellectual personally. Poetry accidentally made possible Prof Kishani’s most concrete and personal connection with me. Langaa Research and Publishing Common Initiative Group (Langaa RPCIG) published my second poetry collection in English, Bites of Insanity, in February 2015. To receive my author copies, I provided Langaa with my postal address in care of Professor Babila Mutia at École Normale Supérieure (ENS) Yaoundé. However, Langaa’s international distributor African Books Collective (ABC) accidentally mailed my two copies to Prof Kinshani instead of Prof Mutia.

Through the postal tracking system, the error was identified and I got hold of Prof Kinshani’s phone number. In our telephone conversation, Prof Kinshani acknowledged that he had received the books and had thought that they were a gift from Langaa to him. And he had gone ahead to write his name in one of the copies. To me, that was normal given that Langaa had published Prof Kishani’s two poetry collections in the past. Prof was in Bamenda at the time while I was in Yaoundé. And he spoke so highly of my poems in Bites of Insanity.

When I informed ABC of the situation, a new copy of the book was mailed to Prof Kishani so that I could collect my two author copies, leaving Prof with the one he had already written his name on. When Prof returned to Yaoundé and I met him, he handed me not only my two copies but also a review he had written for the collection. In his review of Bites of Insanity, Prof Kinshani opined that the collection “…merits more than an award […], especially as it strikes a balance between cultural interplays of creativity and humour, universal exigencies and contemporary tastes and needs…” And Prof agreed with me to send the review to Langaa for publication on their website.

That is how Prof Kishani and I became closely connected by poetry and by extension culture and language. He encouraged me to continue to write poetry, to continue to promote my Mbesa (Mbessa) language as I was already doing, etc. When I met him in 2016 to inform him that I was travelling for further studies in Europe, he was so happy and gave me many pieces of fatherly advice. He then spoke of how he was seeing some similarities in Prof Bernard Fonlon and my humble self, and he pleaded with me to make sure I laid hands on Prof Fonlon’s PhD thesis while in Europe so that Cameroonians could also access it.

Little wonder that Prof Kinshani gave me this task given that he was the first son of Nso and Cameroon to discover where Ngonso (Ngonnso) had been stolen and “abandoned to strange gazes in Germany” (Mbuh 2024). Sadly, Ngonso will return home in Prof Kishani’s absence!

Once in Europe, I took Prof’s plea seriously and entered into correspondence with University College Cork (UCC) in Ireland where Fonlon had submitted his PhD thesis in French entitled La poésie et le reveil de l’homme noir, becoming the first Anglophone Cameroonian to earn a doctoral degree in 1960. My contacts at UCC, especially in the French Department where Fonlon did his research, were very willing to release a copy of the thesis for Cameroon through my initiative. We corresponded for about a year. But we came across an obstacle: copyright law at the time Fonlon submitted his thesis in 1960 made it such that he alone could authorise such a move! Prof Kinshani was so disappointed when I relayed this news to him on the phone! His voice was so weak as we spoke, signalling his ill health! And he confirmed to me that his health was increasingly failing.

What we didn’t know was that Prof Fonlon had actually published his thesis as a book under the same title La poésie et le reveil de l’homme with Presses Universitaires du Zaïre in 1978. That reality was off my Internet search radars, strangely so! Fortunately, earlier this year 2024, I was able to lay my hands on a copy of Fonlon’s published thesis thanks to Edward Dzerinyuy Bello and Kijika M. Billa on Facebook. While I was still planning to share the good news with Prof Kinshani, I was so saddened to learn of his passing onto glory yesterday 23 February 2024!

His death is indeed a great loss for Nso, Cameroon, Africa and the cultural-intellectual world!

Indeed, despite his soft spoken and self-effacing nature, Prof Kishani leaves behind an immeasurable creative, cultural and intellectual legacy for Nso, Cameroon, Africa and the world.

Creatively, he was an accomplished poet with many poetry collections to his credit, in both English and Lamnso, including Konglanjo (1988/2010) and A Basket of Kola Nuts (2009) in English, and Kpu e Go’ e Njem (1998) in his native Lamnso. Situated among the first generation of Anglophone Cameroonian poets, alongside contemporaries such as Bernard Fonlon, Mbella Sonne Dipoko and Sankie Maimo, Bangasu Tanla Kishani’s poetry heavily draws on Nso and Cameroonian oral traditions to castigate sociopolitical evils while promoting Cameroonian cultures. Major facets of his life such as his Nso language (Lamnso) and oral-cultural roots and philosophical thought coalesce into his rich poetry oeuvre, valorising cultural artefacts and foodstuffs like the kola nut in intertextual dialogue with other prolific writers such as Kenjo wan Jumbam and Chinua Achebe. Little wonder that in 1990 the Association of Nigerian Authors (ANA) awarded the first position to his 1988 collection of poems, Konglanjo.

His stellar contributions to scholarship ran across multiple disciplines, notably literary studies, gender studies, oral traditions and philosophy. For instance, in his scholarship, Kishani documented and celebrated emblematic historical figures from Cameroon such as King Njoya of Bamum whom he elevated to Fon Njoya the Great, in celebration of Njoya’s iconic civilisational achievements, especially his invention of a writing system (Kishani 2005). In philosophy, Kishani wrote extensively on the language question, arguing for the pivotal role of African languages in vehiculating African philosophical concepts and thoughts, although many scholars criticise this position. Like Ngugi wa Thiong’o in the African literary sphere, Bongasu Tanla Kishani argued that “Africans cannot continue to philosophize sine die in European languages and according to European models of philosophy, as if African languages cannot provide and play the same roles” (Kishani 2001).

In the same vein, while diagnosing language problems on his multilingual Anglophone Cameroonian literary landscape, he described languages of European origin such as English and French as “ephemeral” and suggested that “To choose to write exclusively in a European language as a Cameroon without reservations seems to me to attach too much importance to a language which only enjoys an interim status” (Kishani 1994:102). And he very much walked his talk in this regard. For instance, in addition to publishing a collection of poems in his indigenous Lamnso language and infusing Lamnso into most of his poems in English, he sometimes provided Lamnso translations of his English scholarly abstracts as is the case in his article about the ideological implications of women’s names in Nso society (Kishani 2004). And he translated the Cameroonian national anthem from English into Lamnso.

I could go on and on, but I would never be able to summarise Prof Kishani’s wide-ranging contributions to culture and scholarship in Nso, Cameroon, Africa and beyond. However, before I conclude, a brief biographical sketch of this distinguished poet-scholar is in order.

Bongasu Tanla Kishani was born on 21 June 1944 in Kitiiwum, Nso’, Cameroon. After his primary education in Kitiwum and Shisong, Kishani went to secondary school at St. Joseph’s College, Sasse. He then respectively studied in Nigeria, Italy and France, graduating from the University of Paris, Sorbonne, with a Doctorat de 3e Cycle (1981) and a Doctorat d’Etat-es Lettres et Sciences Humaines (1988) in Philosophy. After working as a Sécretaire de Rédaction at Présence Africaine in Paris, he returned to Cameroon where he taught Philosophy at the University of Yaoundé from 1981. Professor Bongasu Tanla Kishani passed away on Friday 23 February 2024 after a protracted illness. He will be buried on Saturday 23 March 2024 at his Bambili Residence and his traditional mourning rites will take place in his native Ruun Kitiwuum village in Nso Fondom, all in the Northwest Region of Cameroon.

To conclude, I urge everyone of us who shares the philosophical, cultural, literary and scholarly visions of Prof Kinshani to keep Prof Kishani’s numerous publications, scholarly contributions and many other achievements of his in mind as we pray for our Ancestors and God to welcome him while we carry on with his lasting and selfless legacy. Jel-ajung a Prof. Ghan-kijung Prof. Farewell Prof. Adieu Prof.

Works Cited

Kishani, Bongasu Tanla Andrew. 2005. “The Proverbial Philosophy of Fon Njoya the Great.” Présence Africaine, 171(1): 81-109.

Kishani, Bongasu Tanla. 2004. “Ideologies of Women’s Names Among the Nso’ Of Cameroon: A Contribution to the Philosophy of Naming, Decolonization and Gender.” Quest: Philosophical Discussions, 18(1-2): 57-81.

Kishani, Bongasu Tanla. 2001. “On the Interface of Philosophy and Language in Africa: Some Practical and Theoretical Considerations.” African Studies Review, 44(3): 27-45.

Kishani, Bongasu Tanla. 1994. “Language Problems in Anglophone Cameroon.” Quest: Philosophical Discussions, 8(2): 102-129.