National Front has given voice to much of working class once represented by the left. Dangerous ideas stalk the French election campaign.

APRIL 15, 2017 by Michael Stothard in Paris

Sipping a coffee at Le Rouge Limé café in central Paris, Michael Foessel, professor of philosophy at the École Polytechnique, harks back to a time when leftwing intellectuals really mattered.

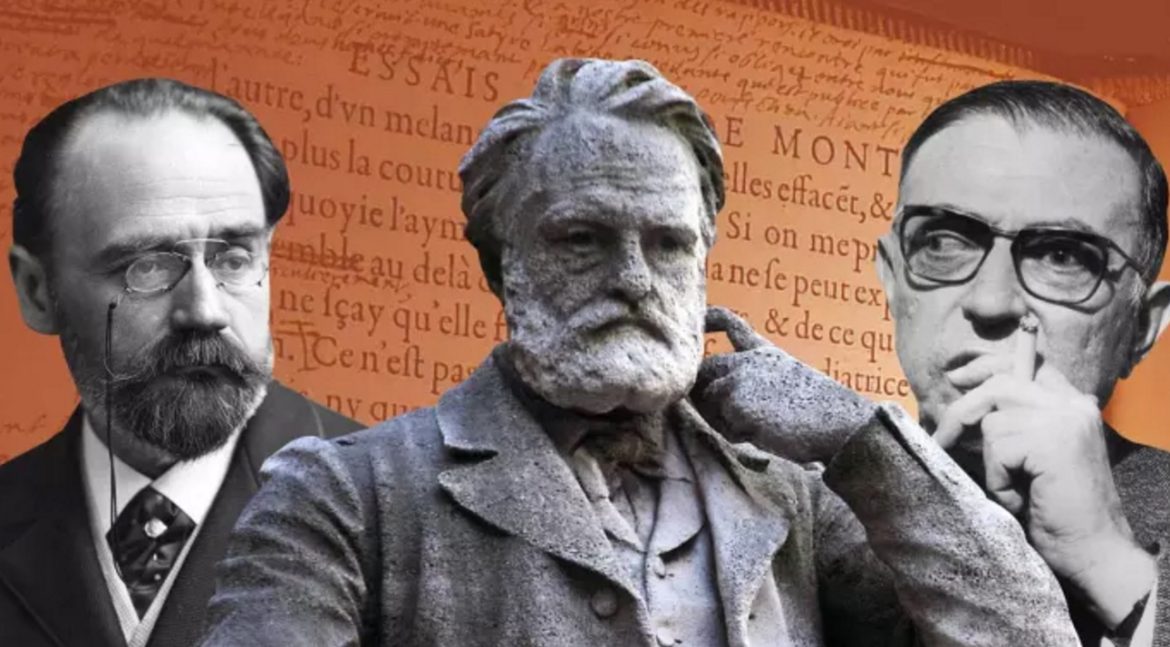

Long gone are the days, he says, of Pierre Bourdieu leading strikes by railway workers, Michel Foucault shifting the debate on prison reforms, or Émile Zola and his plea for justice during the Dreyfus Affair.

“We are no longer the intellectual leaders of this country,” says the 42-year-old, wearing jeans and a tweed jacket. “In the media, it is the conservative voices that make a big impact. In politics, it is the technocrats.”

He is talking just ahead of an election that has been dominated by the rise of populist far-right leader Marine Le Pen, who, through a blend of nativism and economic nationalism, has given a voice to much of the disenfranchised working class once represented by the left.

After five years of unpopular Socialist government under President François Hollande, the party’s candidate for 2017, Benoît Hamon, is set to come fifth in the election on April 23, according to opinion polls. Much of the debate has focused on the traditionally conservative issues of identity and security.

Béziers’ mayor hopes his brand of extreme populism will prove to be a model for a National Front victory

The soul-searching of leftwing intellectuals such as Mr Foessel in part mirrors that of liberal elites across the western world, who are struggling to understand the populist surge that swept Donald Trump to victory in the US and the UK out of the EU.

But the self-examination is perhaps more acute in France, where progressive intellectuals — as far back as Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the 18th century and Victor Hugo in the 19th — have a long history as moral authorities with strong influence over society and politics.

When Jean-Paul Sartre was arrested for civil disobedience during the riots of May 1968, he was such an important figure that President Charles de Gaulle pardoned him, saying: “You don’t arrest Voltaire.”

Even in the 21st century, presidents have taken the advice of intellectuals. Philosopher Bernard Henri-Lévy was involved in France’s decision to send troops into Libya in 2011, lobbying President Nicolas Sarkozy, his friend, to intervene.

“There is a long tradition of power and influence by the intellectual left in France” says Sudhir Hazareesingh, an academic at Oxford university and author of How the French Think. “But their influence has waned in recent years.” France has moved to the political right, says Mr Hazareesingh, with voters becoming more concerned with immigration and questions of French identity.

It rightwinging intellectuals such as Alain Finkielkraut — Mr Foessel’s predecessor at the Polytechnique — who dominate the media landscape, arguing that France is caving in to Islamists in the name of tolerance and liberalism.

Mr Finkielkraut’s 2013 book L’identité malheureuse — The Unhappy Identity — was a bestseller along with Eric Zemmour’s Le Suicide Français. Both dealt with similar themes of national decline and harked back to a golden era.

Michel Houellebecq, an author who has found international success, writes regularly about the rise of Islam. His 2015 book Submission features the election of an Islamist to the presidency.

Marc Crépon, chair of philosophy at the Ecole Normale Supérieure, another elite university, believes the left has been bad at responding to these questions of identity and immigration: “We have left it to the media-friendly right-wingers.”

He stresses the need to reclaim this intellectual ground. Leftwing thinkers such as Zola, Derrida, Camus and Sartre were moral leaders who defended the poor and the weak,” he says. “The left needs to find its voice and its power again.”

Leftwing-wing intellectuals do have an influence on politics, and are on the teams of the presidential candidates, even if most have more in common with experts than the grand philosophers of the 20th century.

Jacques Attali, the social theorist and civil servant, for example, is part of frontrunner Emmanuel Macron’s team, while Thomas Piketty, the bestselling economist, and sociologist Dominique Méda are working with Mr Hamon.

Leftwing-wing authors have also written popular books trying to take on rightwing issues.

For example François Durpaire’s best-selling 2015 comic book, La Présidente, was a thought experiment that imagined Ms Le Pen winning the 2017 election.

While the book was written as a cautionary tale for how the country would be plunged into chaos in such as event, Mr Durpaire says the subsequent rise in support of Ms Le Pen’s National Front has made him question if he really speaks to the majority.

“My book was a warning but, just like in the US and the UK, there’s clearly a huge divide between intellectuals in the big cities and the deep France,” he says. “We are struggling to speak to the people on the other side.”

See online: French intellectuals lament loss of influence as populism surges