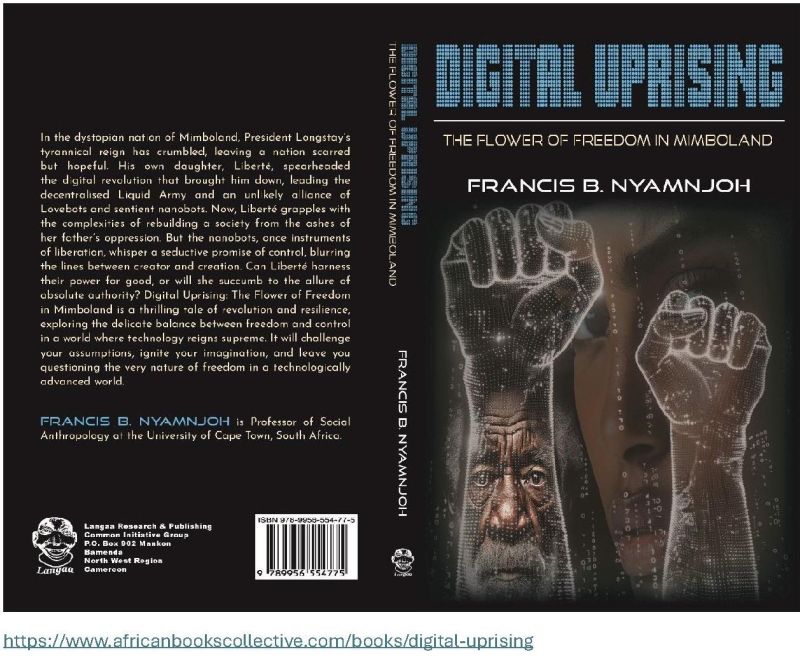

Review of Francis B. Nyamnjoh’s Digital Uprising: The Flower of Freedom in Mimboland, Langaa, 2024, ISBN: 9789956554775, 236 pages.

Reviewer: Dr Hassan M. Yosimbom

Have you ever imagined a world in crisis? Have you conjured a world where the very foundations of democracy and human rights crumble before our eyes? Have you visualized a world where power concentrates in the hands of a select few, leaving the rest to struggle in poverty and despair? This is the stark reality depicted in Francis Nyamnjoh’s 2024 novel, Digital Uprising: The Flower of Freedom in Mimboland. Set in the fictional African nation of Mimboland, the novel paints a dystopian picture where technology becomes both a tool of oppression and a weapon of liberation indicating that in the modern world, there is more to everything than meets the eye; that nothing is connected to everything but everything is connected to something. Nyamnjoh’s idea of the functional duality of technology reminds us that not very long ago, one of the most important United States citizens, Donald Trump, was removed from some social media platforms when he resorted to intermittently using Twitter (now X) to garner political popularity and at the same time oppress and disenfranchise the United States masses.

Nyamnjoh references technology’s double-edged sword incarnated by President Longstay, Mimboland’s tyrannical ruler, who uses technology to maintain his iron grip on the nation. In a manner that is reminiscent of the Big Brother in George Orwell’s1984, he manipulates the masses through propaganda and surveillance, creating a climate of fear and control. However, technology also empowers the resistance movement led by Longstay’s own daughter, Liberté who with her Liquid Army utilise social media, hacking, and even nanotechnology to expose Longstay’s crimes and rally the people against him. Liberté is a character that shocks us to the marrow because she is out of kilter with especially postcolonial African and probably global reality. In a world where even the most incompetent sons and daughters of the most tyrannical leaders usually view succeeding their fathers and mothers either by hook or crook as their God-given inalienable patrimonial right, one wonders from where and how Liberté harnesses the chutzpah to become arguably one of the first daughters of a president to choose justice over patrimony, to choose patriotism over familial personal greed.

Nyamnjoh demonstrates the intimidating power of digital tools. His novel serves as a powerful exploration of the complex relationship between technology, democracy, and human rights. It highlights the potential of digital tools to both enhance and undermine democratic principles. He teaches that these tools can be harnessed to promote transparency, accountability, and citizen participation as much as they can be used to suppress dissent and consolidate authoritarian power. Oppressed communities in many postcolonial nations face a digital double bind: governments manipulate internet access, offering it as a reward while simultaneously using shutdowns and infiltration of online spaces to suppress resistance. And Nyamnjoh does clarify that while the masses often envisage a liberatory interconnection between technology, democracy, and human rights; dictatorial leaderships doublethink and doublespeak that connection, leaving everything to happenstance.

Nyamnjoh’s novel is a global call to action. Digital Uprising challenges us to confront this institutionalized doublethink and doublespeak and consider the implications for our own societies. It underscores the urgent need for critical engagement with digital technologies and their impact on democracy and human rights. By understanding the dynamics at play in Mimboland, we can draw valuable lessons for safeguarding and strengthening democratic values in our own communities. And Nyamnjoh is on point when he references Liberté’s patriotism and not greed-engendered revolutionary example to demonstrate that the real lessons for safeguarding and strengthening democratic values in our own communities need to be backed by charities – like Liberté and her Liquid Army’s pleasant surprise – that commence at presidential palaces and then extend to the whole communities.

Digital Uprising goes beyond the binary because it adopts a gendered lens. The novel also breaks new ground by featuring a female revolutionary leader in a context where such roles have traditionally been dominated by men. Liberté’s courage and defiance challenge gender stereotypes and offer a fresh perspective on the fight for freedom and justice. By creating Liberté and suggesting that a woman can be a mother, politician, socialist, educator, and provider, Nyamnjoh reconnects her to a long line of female revolutionary characters in African literary texts: Beatrice Okoh and Elewa in Achebe’s Anthills of the Savannah; Nyankinyua and Wanja in Ngugi’s Petals of Blood, Jacinta Waringa in Devil on the Cross, and Nyawira in Wizard of the Crow, etc. This connection underscores the ongoing struggle for equality and justice, symbolised by Liberté’s legacy.

Ultimately, by stressing the liberatory as well as the oppressive interconnections between technology, democracy, and human rights, Digital Uprisingis a novel that asks pertinent questions without pretending to provide ready-made answers because it acknowledges that democracy, human rights, and technology are all works in permanent progress.

What happens when society’s formidable weapon such as digital technologies could also be its veritable Trojan horse?

What does a society do when its most trusted ammunition displays a shocking ability to pick and choose from a Jekyll and Hyde personality?

How does a society survive when faced with the stark realization that its unavoidable armament – like the god Ulu in Achebe’s Arrow of God – possesses the enigmatic propensity to destroy a man – as prominent as Donald Trump – the day his life is sweetest to him?

These searing rhetorical questions point to the fact that by the time Digital Uprising comfortably assumes its rightful position on the book shelves of the masses in societies that are experiencing the chokehold of tyranny, it will arguably become one of the most questioned and the most questioning as well as one of the most vexed and the most vexing dystopian novels. And maybe, then, just maybe, we might be called upon to learn or unlearn to showcase our individual digital uprisings by simultaneously reasonably downsizing and downscaling our democracy and human rights nationalisms.

Nyamnjoh’s novel serves as a wake-up call, urging readers to recognise the complex interplay between technology, democracy, and human rights in the digital age.

*Nyamnjoh’s Francis B. Nyamnjoh’s Digital Uprising: The Flower of Freedom in Mimboland is available at Langaa platforms and on Amazon