Why the book endures, even in an era of disposable digital culture.

By Timothy Egan

Not long ago I found myself inside the hushed and high-vaulted interior of a nursing home for geriatric books, in the forgotten city of St.-Omer, France. Running my white-gloved hands over the pages of a thousand-year-old manuscript, I was amazed at the still-bright colors applied long ago in a chilly medieval scriptorium. Would anything written today still be around to touch in another millennium?

In the digital age, the printed book has experienced more than its share of obituaries. Among the most dismissive was from Steve Jobs, who said in 2008, “It doesn’t matter how good or bad the product is, the fact is that people don’t read anymore.”

True, nearly one in four adults in this country have not read a book in the last year. But the book — with a spine, a unique scent, crisp pages and a typeface that may date to Shakespeare’s day — is back. Defying all death notices, sales of printed books continue to rise to new highs, as do the number of independent stores stocked with these voices between covers, even as sales of electronic versions are declining.

Nearly three times as many Americans read a book of history in 2017 as watched the first episode of the final season of “Game of Thrones.” The share of young adults who read poetry in that year more than doubled from five years earlier. A typical rage tweet by President Trump, misspelled and grammatically sad, may get him 100,000 “likes.” Compare that with the 28 million Americans who read a book of verse in the first year of Trump’s presidency, the highest share of the population in 15 years.

“We don’t read and write poetry because it’s cute,” wrote Walt Whitman. “We read and write poetry because we are members of the human race.”

So, even with a president who is ahistoric, borderline literate and would fail a sixth-grade reading comprehension test, something wonderful and unexpected is happening in the language arts. When the dominant culture goes low, the saviors of our senses go high.

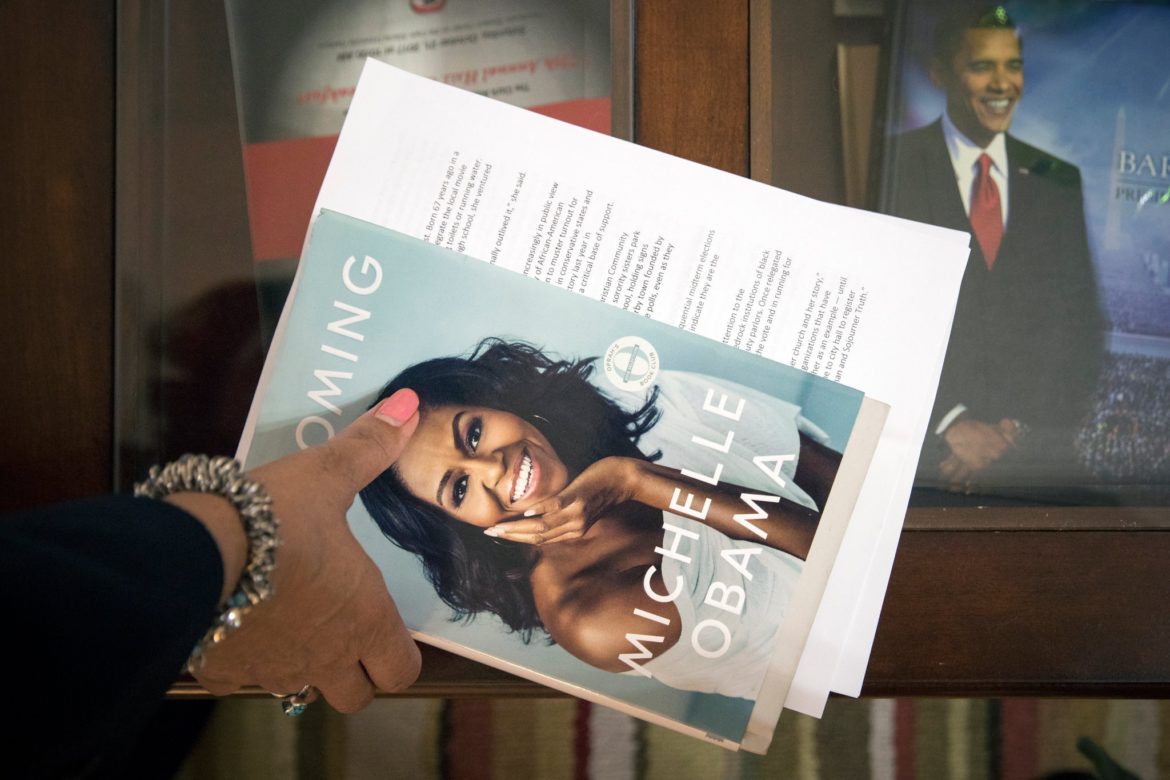

Which brings us to Michelle Obama. You can make a case that we owe a big part of the renaissance of the written word in recent months to her memoir, “Becoming.”

In the first 15 days after publication last year, it sold enough copies to become the best-selling book in the United States for all of 2018. By the end of March of this year, it had sold 10 million copies and was on pace to become the best-selling memoir ever written in this country.

I was late to her book, having my doubts about platitudinous, focus-group-neutered memoirs by political personalities. As it turned out, she’s a luminous, observant, self-aware writer, even if she had some help from a team of ghostwriters. Consider these passages describing her early dance of romance with Barack Obama, when she worked within “the plush stillness” of her Chicago law firm.

“Barack was an ambler. He moved with a loose-jointed Hawaiian casualness, never given to hurry, even and especially when instructed to hurry.”

And here is the effect he had on her: “Until now, I’d constructed my existence carefully, tucking and folding every loose and disorderly bit of it, as if building some tight and airless piece of origami.” But then, “Barack intrigued me. He was not like anyone I’d dated before, mainly because he seemed so secure. He was openly affectionate. He told me I was beautiful. He made me feel good.”

This is old-fashioned storytelling, taking us from an upstairs apartment on the South Side of Chicago to the White House. As someone who makes his living in the business of storytelling, I couldn’t be happier to see her book smash records and help the printed word amble confidently, like young Barack, through another century.

Storytelling, Steve Jobs may have forgotten, will never die. And the best format for grand and sweeping narratives remains one of the oldest and most durable.

But also, at a time when more than a third of the people in the United States and Britain say their cellphones are having a negative effect on their health and well-being, a clunky old printed book is a welcome antidote.

When people go on a digital cleanse, detoxing from the poison of too much screen time, one of the first things they do is bury themselves in a book — that is, one to have and to hold, to remind the senses of touching “Pat the Bunny” in infancy, a book to chew on.

“I think it’s somewhat analogous to what happened with food,” said Rick Simonson, longtime buyer at the Elliott Bay Book Company in Seattle. “We came of age when the commercial messages about food were all to make it instant. Now look at how food has changed ‘back’ — the freshness, the health aspect, the various factors like community.”

While our attention span has shrunk, while extremists’ shouting in ALL-CAPS can pass for an exchange of ideas, while our president uses his bully pulpit as a bullhorn for bigotry and ignorance, the story of our times is also something else. It’s there in the quieter reaches, in pages of passion and prose of an ancient technology.

Timothy Egan (@nytegan) is a contributing opinion writer who covers the environment, the American West and politics. He is a winner of the National Book Award and author of the forthcoming “A Pilgrimage to Eternity.”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.